Credit, for the following information, goes to Rankandfile.ca.

July 15, 1946

The Stelco Steelworkers strike began on July 15, 1946, in Hamilton, Ontario. It was a crucial and bitter battle in the history of the union that lasted 81 days. The strike caused deep divisions in the community and within families. The Ford Windsor strike, the previous fall in 1945, had ushered in a new wave of union victories and employers wanted to stop it. Stelco and an army of 2,000 scabs (strikebreakers), were backed up by the police and the Hamilton Spectator newspaper who were out to break the union and score a major victory for the business class.

The young and untested Steelworkers Local 1005 wanted to ratify a contract that included a 40-hour week, paid vacation, and union dues check-off, which is a collective bargaining clause requiring the employer to deduct union dues. Supporting and backing the union was Hamilton’s mayor, Sam Lawrence, and most of the public that included recently returned WW2 veterans.

On the second night of the strike, Stelco started the violence when 300 scabs armed with rubber hoses, axe handles and bricks attacked picketers that were holding up box cars on the train lines. The picketers fought back by throwing slag and stones at the scabs. In response, CP and CN rail workers refuse to cross the lines, helping the union’s cause. While the union maintained its picketing policy of “nothing in, nothing out”, the company uses boats to bring in supplies. The union responds by organizing its own fleet, including the “Whisper” which was bought from a bootlegger and said to be the fastest boat around Hamilton Harbour. The Whisper was used to intercept strike breakers.

When a freighter loaded with 3,000 tons of scab steel was heading for Montreal, the workers on the Lachine Canal in Montreal refuse to let it through until police got involved. They vowed a major strike up and down the canal the next time scab steel came their way. Support for the strikers continued to spread across the country.

“The Battle of Wellington Street” was another incident where a union flying squad (an unofficial group of workers who carry out actions for their labor struggle) armed with clubs and throwing stones drove off 50 scabs trying to load a boat on the docks. The boat left with nothing. These types of clashes were very common.

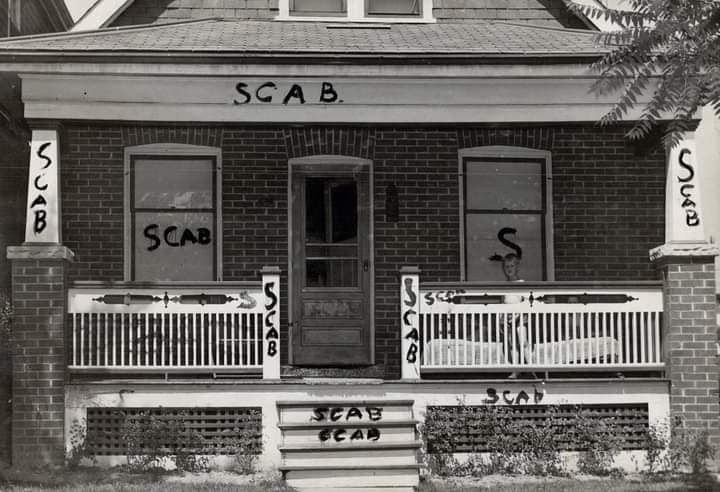

Stelco used an airplane to fly in supplies, but the union’s own Walter Kubeci, a former Spitfire pilot, took to the skies in a plane rented by the union. Kubeci dropped leaflets on the mill calling on the scabs to give up. Scab homes were painted with “SCAB” to make sure everyone knew they were stealing jobs in the cause of union-busting greed. Scab-owned companies were blacklisted and boycotted. Harassment and intimidation of scabs and their families was reported.

At the City Hall, Sam Lawrence took on right-wing pro-company councillors. The pro-union bloc defeated the right-wing effort to call in the notorious strikebreakers, the Ontario Provincial Police.

After the victory at City Hall, the Hamilton police provoked a fight with a mass picket in late August to justify bringing in 500 OPP and RCMP officers. Hamilton restaurant workers responded by refusing to serve police in uniform. Kitchen staff, who worked in police lodging and billets, refused to cook for them.

The OPP and RCMP backed down and never took on the picket lines. They were scared of the local response which was 25,000 people who joined the picket lines in preparation for a police attack. The attack never came. In addition, there was a parade of 10,000 people that marched from Woodlawns Park to the gates of Stelco. It was led by mayor Sam Lawrence and hundreds of veterans marching in formation.

By mid-summer of 1946, more strikes erupted at Westinghouse and other factories. About 1 in 5 of Hamilton’s industrial workers were on strike. Women organized huge food stations to feed the thousands of supporters now on the picket lines. Hamilton’s working class was calling the shots.

With Stelco under siege, scab morale plummeted, and the police cowed. The union won a huge victory with an agreement in the early fall. The strike ended on October 4, 1946. The new deal was ratified 2,173 to 112.

Hamilton’s non-union Dofasco steel mill learned its lesson and maintained wages and benefits competitive with Stelco in order to keep the union out. The Stelco strikers won major gains far beyond their own ranks.

Steelworkers Local 1005 had survived its first real test as a union and defeated Stelco’s union-busting drive.